John Kent Cooke didn’t get his father’s Redskins. He got something better.

John Kent Cooke lives on a 150-acre estate in Middleburg, Va. There’s a lush, 26-acre vineyard on the property that produces Boxwood wines, a project he and his wife, Rita, have been working on for the past 14 years. He also owns newspapers and other media properties in North Carolina and Florida. In winter, he and Rita can be found onboard a classic 57-foot yacht that they moor in South Florida. And at least a few times a year, he travels to Lansdowne, Va., to visit his father’s foundation, set up 17 years ago to provide scholarships to low-income students.

Get the full experience. Choose your plan ArrowRight

It’s a rich, full life — just not the one he had envisioned 25 years ago when he occupied an expansive office at Redskins Park as team president and the presumed successor to his father, Jack Kent Cooke, the franchise’s owner. For years, he was a constant presence there, his father’s stand-in because Jack preferred to work out of his Middleburg farm. John oversaw the finances, stadium operations, office and front office personnel — everything but football. Jack had the ultimate say in hiring the head coach and general manager, though John certainly offered advice.

I first met Jack Kent Cooke in the late 1970s as The Washington Post’s beat writer on the Redskins. And I was still at the paper in 1999 when the family’s tie to the team, which dated to 1961, came to a controversial denouement. That year, acting on Jack’s wishes, the trustees of his estate sold the Redskins and the stadium in Landover, Md., to Daniel Snyder for a reported $800 million and used the proceeds to establish the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation. By doing so, it became virtually impossible for John to keep the team.

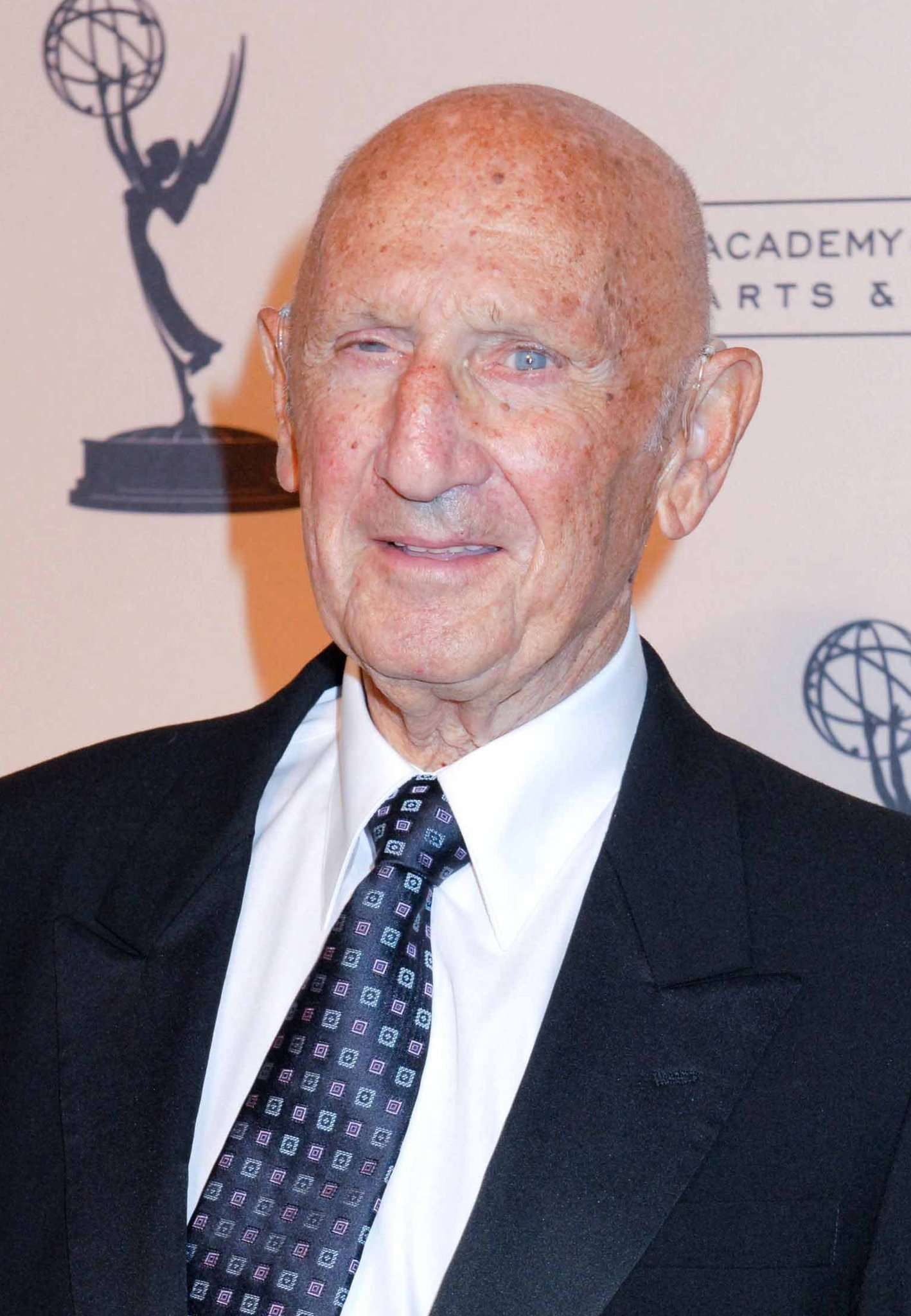

To this day, there are Redskins fans who speculate about what would have happened if the younger Cooke had become the owner. Over the years, he has expressed frustration over the sale of the team. And he has occasionally criticized what has become of the franchise that won three Super Bowls under his family’s stewardship. But John, now 75, said there’s no lingering bitterness over his father’s decision, especially in light of what it has created, something more enduring than trophies or rings.

For those who weren’t here when Jack Kent Cooke died in 1997, it can be hard to grasp how shocking it was when his estate said it was putting the Redskins up for sale. There are even fewer around who remember what Cooke was like.

Advertisement

Cooke was unlike anyone I had ever encountered as a journalist. “This was a self-made man, a bold thinker and brilliant businessman,” I wrote the day after he died, “who could be equal parts charm, culture and charisma while displaying a streak of crude and occasionally cruel incivility, arrogant bluster and unforgiving vindictiveness.”

Born in Hamilton, Ontario, Cooke started selling encyclopedias door-to-door at age 14. In 1936, he was selling soap for Colgate-Palmolive when he met Roy Thomson, who hired Cooke to run his radio station in Stratford, Ontario. The two eventually became partners and started buying newspapers and radio stations. Cooke got involved in sports in 1951 when he bought a minor league baseball team in Toronto. He moved to the United States in 1960 and a year later paid $350,000 for a minority stake in the Redskins. He became majority owner in 1974 and sole owner in 1985. He bought other sports teams, including the Los Angeles Lakers. He also owned the Chrysler Building in New York.

He was a ruthless negotiator and a mercurial man who could go from dead calm to Mount Vesuvius rage in a flash. He also wrote music, read extensively and composed poems for the four women he courted and married. One union lasted only 73 days. The last so-called love of his life, Marlene Chalmers, was known around town as the “Bolivian Firecracker” and liked to party, often without Cooke.

Advertisement

Cooke had two boys, John and Ralph. John was always the good son. When Cooke and their mother divorced, John sided with their father, while Ralph sided with their mother. Because of that, Jack essentially eliminated Ralph from his life for years. They reconciled before Ralph died in 1995 of liver failure at age 58.

John would accompany his father when he met with Post sports editors, columnists and reporters every year before the start of training camp. During those sessions, Cooke would call him “my dear boy” or “Johnnycakes” or even “Cakes,” making anyone who heard it rather uncomfortable. Cooke did all the talking; John rarely spoke in those situations. Still, they were close. John lived on a farm about five miles from his father’s Middleburg estate. Any time Cooke came out to Redskins Park, John was by his side.

John clearly admired his father’s business acumen, calling him “a natural-born salesman. He really was quite amazing.”

Advertisement

Jack Kent Cooke once told the late sportswriter Morris Siegel, his on-again, off-again pal, that he had no intention of ever dying and didn’t like to go to funerals because they reminded him of his own mortality. When Siegel died in 1994, Cooke was true to his word and was a no-show at the funeral.

“I want to be buried in a burgundy-and-gold coffin,” Cooke said in 1992. “And when I’m gone, someone named Cooke is going to run this team. And when he’s gone, someone else named Cooke is going to run this team.”

Instead, however, he reportedly changed his will eight times over the last 10 years of his life. In the original version, Ralph was to inherit Elmendorf Farm, a thoroughbred horse-breeding operation in Lexington, Ky., and John was to get the team. Cooke also fathered a daughter, Jacqueline, at age 75, with his third wife, Suzanne Martin. He left Jacqueline a $5 million trust fund, but she was never considered for ownership of the team. (She’s now 29 and works in New York in the fashion industry.)

Advertisement

Then in 1993, Cooke wrote John out of the will as his successor in charge of the franchise and never put him back in.

In interviews with several of Cooke’s friends, a few factors in his decision emerge. For one, they said, Cooke was not certain that John was up to keeping the franchise among the elite teams in the National Football League, or even that John would have been totally committed to the task. And if the Redskins had faltered under John’s leadership, Cooke told one friend, “ ‘My own legacy would have been diminished over time.’ Jack was worried about his own reputation.”

He also wanted to endow the foundation with enough funds to be a world-class operation and assure that he would be remembered as a great philanthropist. “He wanted his legacy to be the foundation, and giving the team to John would have interfered significantly,” said the friend, who asked not to be identified in order to speak freely about the family dynamics. “It was about Jack Kent Cooke. It always was.”

Advertisement

John Cooke disagrees with those who say that his father didn’t think he was up for the job of owner. He also said his father often talked about giving scholarships to poor students.

“Dad always revered education, I think, because he didn’t get it. He never graduated from high school,” John said during a recent visit in the spacious office attached to his main residence. “He’d always say, ‘What could I have accomplished if I’d gone to college?’ ”

So when Cooke told John about his plans to sell the team two years before he died, John was not surprised.

“He wanted to for his own satisfaction,” John said. “He also was very practical. The taxation [on his overall estate] would have been tremendous” — in 1999, the inheritance tax was 55 percent — “and at the time, the estate wasn’t really as large as it had once been. . It was understandable why he made the decision.”

Advertisement

John said he and his father kept discussing the possibility of keeping the team in the family even in the final months of his life.

“Dad was not healthy at that point,” John recalled. “He was in a wheelchair. He couldn’t walk. There were doctors galore, therapists, nurses, 24 hours a day. He was still mentally okay, but he was also worried. I don’t know if he knew he was dying. But I realized he wasn’t going to live much longer.”

At the time, the NFL had a new policy allowing a 20 to 30 percent shareholder to own a franchise with partners. John thought it improved his chances of buying the team and told his father.

“He had not been aware of that and said he would look into it,” John said. “Unfortunately, we just ran out of time.”

Jack Kent Cooke died from congestive heart failure in April 1997. He was 84. His final will stipulated that the bulk of his estate, which Forbes magazine estimated at the time to be worth about $800 million, be used to set up the foundation that now bears his name. He had taken some delight in knowing his decision would shock people. He once told Siegel: “My will, dear Morrie, is a magnificent surprise.”

Advertisement

John, with support from what he described as several “wonderful partners,” then made a bid for the team that in the end, he said, reached about $750 million — well short of Snyder’s $800 million.

The trustees were obligated to get the best price. John felt that the NFL owners could still have awarded him the team but didn’t because of fear of a court battle.

“One of the reasons the trustees gave it to Snyder was that they were worried about a lawsuit,” he said. “I do believe that if I had retained the Redskins, the foundation still could have been born and would have been as world famous as the Redskins were. Both things could have been accomplished. . In my opinion, the sale was totally botched.”

Today, the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation is housed in a gleaming metal and glass building tucked in an office park off Route 7, near Leesburg. A mounted bronze sculpture of Cooke can be found near the lobby, and photographs and other memorabilia from his life donated by John are scattered about.

Advertisement

The only way to judge whether Jack Kent Cooke’s final act of egotism and generosity was worth depriving his only living son of the team he loved is to look at what it has wrought. Since its inception, the foundation has awarded more than $150 million in scholarships to roughly 2,200 students. Many Cooke Scholars grew up in families well below the poverty line and might never have been able to continue their educations without the foundation’s help. That level of support should be available virtually in perpetuity. The foundation had net assets of $634 million as of May 31, according to its annual report.

Raul Mateo Magdaleno is one of its beneficiaries. Born in a small village in Mexico, he was one of 10 siblings. His undocumented family came to the United States when he was 18 months old, settling in an East Dallas neighborhood beset by gangs, drugs, shootings and lousy, underfunded schools. His father went to prison and died when Raul was 3. His two brothers were also incarcerated, and six of his sisters dropped out of high school.

At age 19, he was supporting his disabled mother and a mentally challenged sister by working more than 40 hours a week as dispatcher for AT&T, living with them in a homeless shelter and attending Mountain View community college full time. His work shift was 5 p.m. to 4 a.m. four days a week. The other three, he went to school. Many days, he slept in his car before class.

His dream college was Southern Methodist University in a posh section of Dallas. Tuition at the time was over $40,000 a year.

Magdaleno learned of the Cooke scholarship online. Winning it “felt like I hit the lottery,” he said. “What an unbelievable difference it made in all of our lives.” He quit his job, moved his mother and sister in with him in a studio apartment, and paid his sister’s medical bills.

After graduating in 2006 at the age of 26 with a degree in corporate communication and public affairs, Magdaleno was offered a job with a major Dallas bank and a generous starting salary but instead stayed at SMU to set up the first Office of Diversity and Community Engagement. He ran it for five years, focusing on recruiting and retaining minority and low-income students. He eventually started his own company and the Magdaleno Leadership Institute, a nonprofit organization that helps low-income students go to college.

Larry Thi’s life was also transformed by a Cooke scholarship. He grew up in Philadelphia, raised by a single mother from Vietnam who was widowed when her husband died of a cocaine overdose when Larry was 9. The family shared a cramped basement apartment with an aunt. Larry and his two siblings slept in the same bed, under a drooping ceiling. “I always used to ask [my mother], ‘Are we getting richer or are we getting poorer?’ She’d always say, ‘We’re getting poorer, but you are the future of our family,’ and I always believed her,” he said.

By high school, Thi started thinking he could be the first in his family to go to college. Maybe even Harvard. Then he took his college entrance exams. He still remembers the scores: 25th percentile in verbal, 66th percentile in math, 10th percentile in writing.

His first year at community college, he tried registering for five classes but was told he could take only four until he proved himself a worthy student. “It was the first time in my life I’d ever been told, ‘You missed the cut,’ ” he said. Thi worked on improving his grades and later won a Cooke scholarship, which allowed him to finish his degree at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Afterward, he returned to Philadelphia to work for 12+, a nonprofit that encourages low-income students to pursue a college education. He is now an alumni and outreach associate at the Cooke Foundation. “No matter how far up the ladder you go,” he said, “you can’t ever forget the people you left behind.”

A recent Cooke Foundation study found that only 3 percent of students at America’s most selective colleges and universities come from the poorest 25 percent of families. In contrast, 72 percent come from the wealthiest quartile of families, meaning there are 24 “wealthy” students for each low-income student. That disparity can lead low-income students to underestimate their chances for success, said the foundation’s executive director, Harold O. Levy, who was chancellor of New York City schools for nearly three years starting in 2000. “When a low-income kid gets a bad grade, he immediately thinks, ‘I don’t belong,’ ” Levy said. At a recent weekend retreat for Cooke Scholars, he asked students to raise their hand if they thought the foundation had made a mistake in choosing them. Every student raised their hand, he said.

Levy never knew much about Jack Kent Cooke until the foundation recruited him. But he admires the way Cooke set it up, even if that meant selling the football team he said would always be in his family. “Whatever else he did with his life, however hard-charging he was,” Levy said, “he left behind an important legacy that will live on for generations.”

John Cooke joined the board of his father’s foundation as soon as it was formed in 2000. But, devastated after losing the team, he moved to Bermuda for two years.

The Redskins went on to finish last in their division eight times over the next 17 seasons with just one postseason victory. They have cycled through eight head coaches over the same span. Some fans came to revile Snyder as a toxic meddler quick to pull the trigger on firing head coaches, signing big-contract, big-bust free agents and putting the wrong people in positions of authority.

As the team struggled, John became a vessel for speculation among fans like Adam Banig, who writes about the Redskins on a website called Blog So Hard.Banig has no doubt that the past two decades of futility and frustration on and off the field might have been different with John as the owner. “I’m 37. I still remember when the Cookes owned it and things were done really well,” he said. “Lately, Snyder seems to be on the right track, but when he first owned it . he didn’t let his football people do their jobs. If John had gotten the team . there would have been stability. . There were a lot of wasted years.”

But for John, the time for what-ifs has passed. There was no single turning point. He ran his media businesses, threw himself into the winery and helped oversee the foundation.

John has been “extremely supportive,” Levy said. “At critical moments, he is right there. When I was being interviewed [for the job], he was right there. When we do budgeting, he is right there.”

These days, John looks fit and healthy. He travels extensively, loves the water and prides himself on his prowess around boats. Somewhat soft-spoken and mild-mannered, he and his wife maintain a low profile in Middleburg.

He’s exceedingly pleasant and particularly modest about what he’s accomplished with the winery and his media holdings. He’s also terribly proud of his children, including stepdaughter Rachel Martin, who runs the winery.

What would Jack Kent Cooke think about the foundation if he could see it now?

“If he saw the building, he’d probably say, ‘Why the hell did you spend all that money on this?’ ” John said, laughing. Then he paused to reconsider.

“No, really, I think he’d be thrilled.”

Leonard Shapiro is a former Washington Post sports reporter, columnist and editor. To comment on this story, email wpmagazine@washpost.com or visit washingtonpost.com/magazine.

For more articles, as well as features such as Date Lab, Gene Weingarten and more, visit The Washington Post Magazine.

Follow the Magazine on Twitter.