Memories of Life on an ‘Atchafalaya Houseboat’

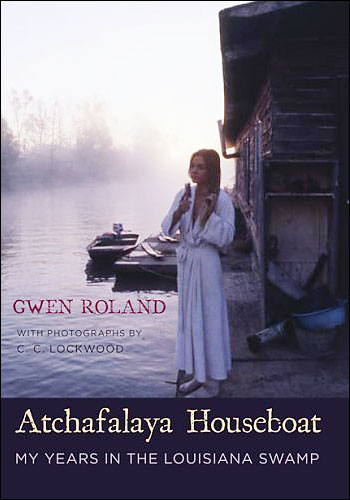

In the 1970s, Gwen Carpenter Roland was about to start work on her doctorate when she decided instead to live off the land — and water — in the Atchafalaya River Basin Swamp in south-central Louisiana.

With a box of crayons and the book How to Build Your Home in the Woods, Roland and her then-partner, Calvin Voisin, built a houseboat on a barge. They lived there for six years, with no electricity and no running water.

Roland has written a book about the experience, Atchafalaya Houseboat: My Years in the Louisiana Swamp. She talks to Melissa Block about existence in the swamp — the everyday routines and the unexpected pleasures — and how she views that part of her life now.

Web Resources

Atchafalaya Houseboat

My Years in the Louisiana Swamp

by Gwen Roland and C. C. Lockwood

Hardcover, 161 pages |

close overlay

Buy Featured Book

Title Atchafalaya Houseboat Subtitle My Years in the Louisiana Swamp Author Gwen Roland and C. C. Lockwood

Your purchase helps support NPR programming. How?

Excerpt: ‘Atchafalaya Houseboat’

April 27, 2006 12:22 PM ET

Photographer C.C. Lockwood chronicled Gwen Roland and Calvin Voisin’s life in the Atchafalaya River Basin Swamp. Lockwood’s photos, published in National Geographic magazine, introduced the world to the idealistic and unorthodox couple.

The original photographs Lockwood took were in color. But in Roland’s book, they are published in black and white. The images below are Lockwood’s originals, with the captions that accompany them in Atchafalaya Houseboat.

“Calvin designed the bed that dropped from the ceiling in a complicated array of pulleys, fishing twine, and mosquito netting.” C.C. Lockwood hide caption

toggle caption

“Calvin designed the bed that dropped from the ceiling in a complicated array of pulleys, fishing twine, and mosquito netting.”

“Weeks spent chopping mortar off of 1,500 bricks seemed worth the effort once the library was finished.” C.C. Lockwood hide caption

toggle caption

“Weeks spent chopping mortar off of 1,500 bricks seemed worth the effort once the library was finished.”

“C.C. (Lockwood, second from left) and Alcide (Verret, at right in enlargement) join us for tea and cookies on a Sunday afternoon.” C.C. Lockwood hide caption

toggle caption

“C.C. (Lockwood, second from left) and Alcide (Verret, at right in enlargement) join us for tea and cookies on a Sunday afternoon.”

“Like our ancestors on Bayou Chene, we made rafts and plank walks for our chickens.” C.C. Lockwood hide caption

toggle caption

“Like our ancestors on Bayou Chene, we made rafts and plank walks for our chickens.”

“A beautiful imported pest, water hyacinths blanketed the coves and choked bayous. Just getting to out crawfish traps could be a day’s work.” C.C. Lockwood hide caption

toggle caption

“A beautiful imported pest, water hyacinths blanketed the coves and choked bayous. Just getting to out crawfish traps could be a day’s work.”

“Reading and writing between net runs were luxuries of wilderness living.” C.C. Lockwood hide caption

toggle caption

“Reading and writing between net runs were luxuries of wilderness living.”

Chapter 9: The Trip

“What day is it, you reckon?”

I stop in midhonk and pound my harmonica on my thigh. A grunt comes from somewhere in the mound of hair dozing in the swing. Let’s see, if it came from the blond end Calvin was responding to my question. If it came from the spotted end Emmy was just woofing in her sleep. I continue gazing at the passed out pair and wait. Then the beard definitely moves, “Monday, maybe?”

Well, that’s a start. Honking softly, I cross the porch to the three calendars hanging among the hip boots and life jackets. Remember the Red River Valley, valley, val-ley, ley. That note’s just not on here, and all these calendars show different months. I consider the possibilities and choose the latest one. Then I play another chorus hoping to sneak up on val-ley while studying all the Mondays in the month as if the right one will identify itself.

There must be a more scientific way. The moon! The moon is decreasing from half. That will at least tell me the week, if I have the month right. But a search of the three calendars reveals only that none of them show the moon stages. While I’m contemplating why someone would print a calendar lacking moon stages, the beard moves again. “Hoover ran his nets today, so it must be Thursday.”

These words of enlightenment fade into a heavy of exertion, which fades into a snore. I return to my lonely contemplation of the calendars. If my calculations are correct, then next Tuesday is “Going-In Day.” Only four more days of freedom left.

The biggest inconvenience to living so far out is going in. The impending trip casts its gloomy shadow over our normally unstructured days. The list, an innocent-looking sheet of typing paper, appears on the kitchen table where it assumes temporary control over our lives. It is divided into categories such as mail, camera store, feed store, welding supply store, hardware store, garden supply store, supermarket, library, people to see, eggs to deliver.

For the next several days our activities revolve around that silent taskmaster. We hunt up the ice chest for transporting cold foods on the long journey home. A crate is readied for a sick chicken headed for LSU’s poultry science department. A broken pump part is placed on top of the list so it won’t be forgotten. Mail that was picked up during the last trip must be answered before we leave home. Despite our good intentions mail is always neglected until the night before the trip. By lamplight we struggle to write legible letters, and we search with candles for lost addresses.

The dreaded day creeps over the horizon in a drizzle. What a waste of a fine rainy day! We usually greet such a morning with a second pot of coffee and a stack of old National Geographic magazines.

I feel a toothache coming on. When I sit up, a wave of dizziness washes over me. As soon as my foot touches the floor, I’m convinced I have an ingrown toenail. I groan and fall back in the bed. A person in my condition can’t be expected to travel.

Calvin, an expert at handling my symptoms, brings me a cup of coffee and says, “You stay right here. I can handle the trip alone if you feel bad.”

Instant remission of all symptoms. At first I snuggle back and sip contentedly. But after that initial relief, poignant tableaus begin nibbling at my conscience. Calvin waving good-bye through the rain. Calvin hauling all the empty gas tanks over the levee. Calvin facing shop clerks, postal regulations, and traffic all alone. Reluctantly I decide that perhaps I’m strong enough to travel. After all, a guilt trip alone is much worse than a trip into civilization with company.

Dispiritedly I dress for the trip. Pastel summer dresses will be splashed with fishy water and splotched with gasoline after ten bouncing miles over open water. Girlish shoes twist treacherously in a slippery boat and sink in the mud at the landing. The bulk of my hair arrives flat and creased from being jammed under a welder’s cap while the ends that leaked out are tied in dozens of tiny knots.

If there is room in the boat for a lard can containing civilized clothes, I can dress sensibly for the ride in jeans and rubber boots, changing in the urine-scented bushes at the landing where we and other travelers have emptied our bladders for years. Winter adds to the confusion with insulated boots, quilted underwear, snowsuits, hats, and gloves that will be removed at the landing and stuffed in the truck.

The boat ride varies from twenty minutes in daylight to an hour in fog or darkness. The entire trip is planned around the futile goal of getting back to the landing before dark. To relieve the boredom of the ride, I read old newspapers that are brought along to help keep us dry. The pages flap and wave and wrap around my head as I try to finish a story before the paper gets so soggy that it falls apart and the tale is lost forever.

At the landing we scramble up the muddy willow roots time and again with ice chests, disintegrating egg cartons, smeared mail, several gas tanks, a wet sick chicken. As we bump along to the Bayou Sorrel Trading Post where Miss Julia keeps our mail in a cardboard box, I try to civilize my appearance in the rearview mirror. No matter how well I think I’ve done, we will get stares from strangers during the day that let me know we still don’t look like everyone else. I’ve never figured that out.

We already sit ankle deep in junk mail from the last trip, and now Calvin returns from Miss Julia with another two weeks of mail, which he dumps in my lap as we drive toward Plaquemine. Ads for credit cards, commemorative plates, and medical encyclopedias are added to the pile climbing toward my knees. Mail to be kept is tossed on the dashboard to be brought home and dealt with before the next trip.

After the tedium of the boat ride and the excitement of mail, we reach Plaquemine with headaches and growling stomachs just in time for the morning rush traffic to Baton Rouge. We fill up with gas and a fast food restaurant breakfast before tackling the list. By 9:00 A.M. on this cloudy morning, Calvin, who can steer a boat over open water in bright sunlight without squinting, is crying for his sunglasses. He claims Baton Rouge makes his eyes hurt. Rummaging through the bottles, papers, clothes, and egg cartons I find them under the chicken crate and place them on his nose to relieve his agony.

By noon our list is not half finished and our feet ache all the way up to our hip joints from the unaccustomed hardness of pavement and concrete. By late afternoon our list is slowly whittling down, but so are we. Once again nightfall beats us to the landing. Rain is still drizzling as I wade into the boat and start bailing while Calvin unloads the truck. Down the muddy willow roots we slide with sacks of chicken feed, tanks of gas, boxes, and bags. If it’s winter we gather up the boat-riding clothes and try to master buttons, zippers, rights and lefts in the dark.

Finally the roar of our motor signals the end of our enslavement to the list, and the night wind dissolves the aches and pains we have spent the day collecting. We still have a dark ride ahead and a boat to unload when we get there, but we are free again. The rain stops, and I stretch out on the sacks of chicken feed just as the last of the clouds unravel and disappear. I see nothing but stars above the black tree line. The vibration of the rushing water massages peace back into my body and lulls me to sleep. My closing eyes catch a gleam of white in the darkness. For the first time today the beard is grinning.

Reprinted by permission of Louisiana State University Press from Atchafalaya Houseboat: My Years in the Louisiana Swamp by Gwen Roland. Copyright 2006 by Gwen Roland.