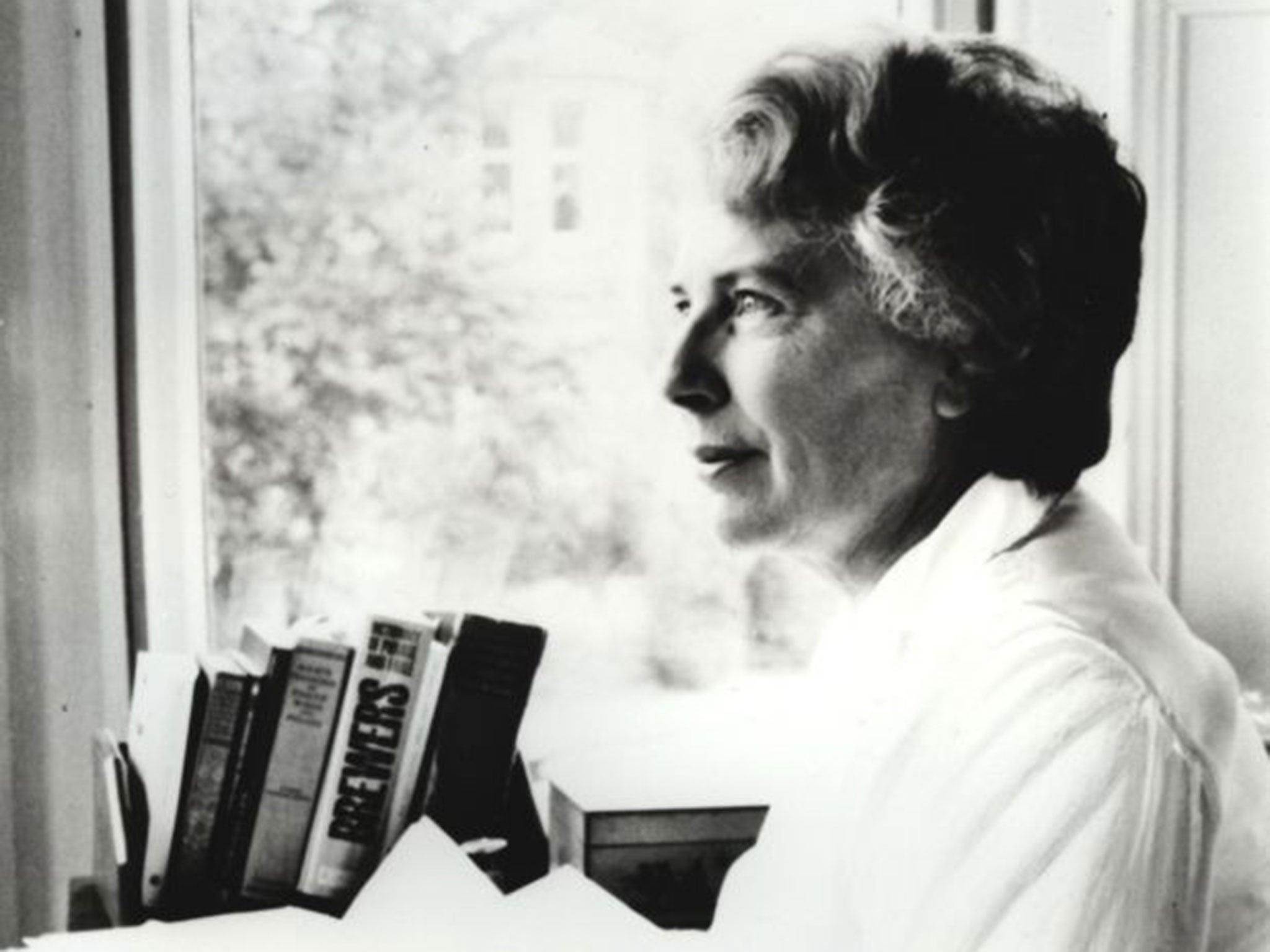

Mary Stewart obituary

The stylish, educated novels of Mary Stewart, who has died aged 97, charmed two generations of postwar readers and launched a whole new strand of modern popular writing: romantic suspense. She arguably inspired the deluge of bestselling romantic fiction that has flooded the market in recent decades. During a writing career of more than 40 years, she produced a score of chart-topping novels that sold in excess of 5m copies and made her an international household name.

Yet fame was not what she wanted. She detested the intrusions it brought and fiercely protected her privacy. In 1997, apprehensive about a forthcoming – and rarely granted – press interview, she found herself unable to write for six weeks. When her first novel, Madam, Will You Talk? (1954), was published and she saw “This is the new star” printed next to her publicity photograph, she burst into tears of dismay.

Stewart introduced a different kind of heroine for a newly emerging womanhood. It was her “anti-namby-pamby” reaction, as she called it, to the “silly heroine” of the conventional contemporary thriller who “is told not to open the door to anybody and immediately opens it to the first person who comes along”. Instead, Stewart’s stories were narrated by poised, smart, highly educated young women who drove fast cars and knew how to fight their corner. Also tender-hearted and with a strong moral sense, they spoke, one felt, with the voice of their creator. Her writing must have provided a natural form of expression for a person not given to self-revelation.

Madam, Will You Talk? featured a woman lured into danger by her concern for a motherless boy. It was an immediate success. Over the next 15 years, a whole line of novels of a similar suspenseful nature rolled out, with titles including Nine Coaches Waiting (1958), My Brother Michael (1959) and The Ivy Tree (1961).

Then came a change of direction. The Crystal Cave (1970), the first of a fictional trilogy about Merlin, arose from her fascination with Roman-British history. The unexpected switch at first alarmed her publishers – she was, unusually, published by the same firm, Hodder & Stoughton, for her entire career, never using an agent – but the book was a No 1 bestseller for weeks.

Of all her books, The Crystal Cave is the most enduring, and has lost none of its freshness. It is a masterful imagining of Merlin’s upbringing that vividly evokes fifth-century Britain. The Hollow Hills (1973) and The Last Enchantment (1979) completed the trilogy, earning Stewart favourable comparisons with another leading Arthurian, TH White. They were the books of which she was most proud.

Stewart’s fans were above all attracted to her wonderful storytelling, which she saw as a skill she was born with – “I am first and foremost a teller of tales” – but also by the warmth and vivacity of her characters and the sharply drawn settings. These ranged from Skye with icy mist coiling around the Cuillin mountains in Wildfire at Midnight (1956) to the searing heat of Corfu in This Rough Magic (1964), with its echoes of The Tempest.

Stewart’s classical education served her splendidly. Informed by lightly worn research, her books were intelligent and full of literary allusion. It might be said that in subject matter and treatment she was a natural successor to Jane Austen and Charlotte Brontë. As the Herald commented in 2004: “She built the bridge between classic literature and modern popular fiction. She did it first and she did it best.” Four children’s books, including Ludo and the Star Horse (1974) and a book of poetry, joined her oeuvre, and The Moonspinners (1962) reached a wider audience through the 1964 Walt Disney film with Hayley Mills and Joan Greenwood as a young woman and her aunt visiting Crete.

Born Mary Rainbow in Sunderland, she learned to read at three in Trimdon, where her father, Frederick, was vicar. By seven, she was writing stories about her toys. Mary and her brother, Gerald, played together in the attic. “Nobody bothered to entertain us; we entertained ourselves. So I wrote,” she said.

At eight she was sent away to boarding school, an experience that marked her for life. She was bullied because she was clever. Her mother, Mary Edith (nee Matthews), from New Zealand, eventually moved her to another school, but she was still unhappy. Even in later years, Stewart would say: “It does stay with you all your life. I still have no confidence. If someone’s unkind, even faintly unkind, you shrivel.”

When she left school, she favoured the idea of being a painter, but the family had limited means and her mother advised that she equip herself to earn a living. Oxford, Cambridge and Durham universities all offered her a place, but Durham gave the best bursary. She graduated from there in 1938 with first-class honours in English. A teaching diploma followed.

During the second world war she taught in Middlesbrough, where children were not allowed to assemble in schools, so she trudged grimly from house to house in all weathers, teaching a gaggle of children who had gathered in one mother’s kitchen before going on to the next to repeat the lesson. More enjoyable was a job in Durham educating troops posted nearby.

Just after VE Day in 1945, she experienced the very stuff of romantic fiction. At an impromptu fancy-dress party at Durham Castle, she met Frederick Stewart, a young Scot who lectured in geology. “He was wearing a girl’s gym tunic, lilac socks, dance pumps … a red ribbon round his head,” she recalled. “He said ‘May I have this dance, Miss Rainbow?’ and I thought ‘You’re the one!'” Three months later they were married.

In 1956, they moved to Edinburgh, where he became professor of geology and mineralogy, and one of Britain’s foremost scientists. In 1974 he was knighted and she became Lady Stewart. The couple lived together until his death in 2001.

At the age of 30, Stewart suffered an ectopic pregnancy, undiagnosed for several weeks. Peritonitis set in and she nearly died. It was a long time before she accepted childlessness. “For years, every single month I thought, perhaps this time. I wanted four. I even had the names chosen.” Her husband was scared of adopting. But there came consolation. “I don’t suppose I’d have written books if I’d had them,” she reflected much later.

She returned to work part-time as a lecturer, but yearned to write. Encouraged by her husband – always her first reader – she constructed a novel. This was submitted to Hodder & Stoughton as Murder for Charity by Mary Rainbow. Hodder liked neither the title nor her pen name, but they loved the book and paid her £50 for it. She did not look back after that, turning out her work first on a heavy manual typewriter that wrecked her wrist, then on an electric typewriter that she disliked because it ran ahead of her thoughts. After a period of dictating to a machine, she settled on a word processor.

The writing had to fit around myriad domestic tasks and the travel and entertaining required by her husband’s position. They divided their home life between Edinburgh and a Victorian house by Loch Awe in the Highlands, with distracting views of snow-capped mountains.

They shared a love of nature and Greek and Roman history, music, theatre and art, all evident in her books. She was a fine cook. The Loch Awe house was furnished with a piano, embroidery, knotted rugs and drawings of their many pets. In later years she lived in Edinburgh.

She is survived by four nieces, Jenny, Elizabeth, Anne and Tricia, and three nephews, Frederick, Martin and Stewart.

Mary Florence Elinor Stewart, author, born 17 September 1916; died 9 May 2014